- Home

- Colm Toibin

Synge

Synge Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Authors

Illustrations

1 New Ways To Kill Your Mother ~ Colm Tóibín

2 A Gallous Story and a Dirty Deed: Druid’s Synge ~ Fintan O’Toole

3 Shift ~ Hugo Hamilton

4 A Glass of Champagne ~ Marina Carr

5 A White Horse on the Street: Remembering Synge in Paris ~ Vincent Woods

6 Driving Mrs Synge ~ Sebastian Barry

7 Locus Pocus: Synge’s Peasants ~ Mary O’Malley

8 Apart from Anthropology ~ Anthony Cronin

9 Bad At History ~ Anne Enright

10 Collaborators ~ By Joseph O’Connor

11 Wild And Perfect: Teaching ~ The Playboy of the Western World ~ Roddy Doyle

When the Moon Has Set

Endnotes

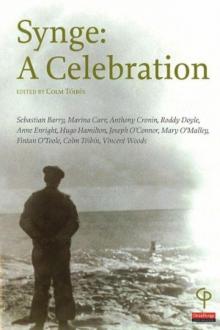

Synge: A Celebration

Edited by

Colm Tóibín

A Carysfort Press Book

~~~~~

J.M. Synge and Molly Allgood. Níl sí ag Eisteacht by Sean Keating PPRHA. Reproduced by kind permission of Sir and Lady A.J. O’Reilly. Copyright permission granted by the Keating Estate.

~~~~~

First published in Ireland in 2005 as a paperback original by

Carysfort Press, 58 Woodfield, Scholarstown Road, Dublin 16, Ireland

© 2005 Copyright remains with the authors

Typeset by Carysfort Press

Cover design by Alan Bennis

Digitized by Green Lamp Media

The publication of this work was supported by a grant from the Arts Council’s.

Caution: All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be printed or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers.

This paperback is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated in any form of binding, or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks, at the beginning, to Lilian Chambers and Dan Farrelly from Carysfort Press for their kindness and patience and careful hard work. Also, to Rupert Murray, Fergal McGrath and Thomas Conway from Druid for the above in equal measure. Then to Michael Stack, who worked as editorial assistant, for his patience and diligence. Also, to the Trinity Library and staff. We are also indebted to Éimear O’Connor for her generous endeavours in acquiring permissions to use Sean Keating’s painting for the frontispiece. Finally, to a number of scholars who have written on the life and work of Synge, and whose books and essays have been invaluable to us in the making of this collection, especially Ann Saddlemyer, Andrew Carpenter, W.J. McCormack, Declan Kiberd, Nicholas Grene and Roy Foster.

Authors

Sebastian Barry was born in Dublin and educated at Trinity College Dublin. He has been Writer Fellow, Trinity College Dublin, during 1995-1996, and has won numerous awards. His novels include Macker’s Garden (1982), Time Out of Mind (1983), The Engine of Owl-light (1987), The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty (1998), Annie Dunne (2002), A Long Long Way (2005). His plays include Prayers of Sherkin (1991), The Only True History of Lizzie Finn (1995), The Steward of Christendom (1995), Our Lady of Sligo (1998) and Hinterland (2002). He lives in Wicklow and is a member of Aosdána.

Marina Carr grew up in Co. Offaly. Her main theatrical works include Low in the Dark (1989), The Deer’s Surrender (1990), This Love Thing (1991), Ullaloo (1991),The Mai (1994), Portia Coughlan (1996), On Raftery’s Hill (1996), and Ariel (2002). Her awards include The Irish Times Best New Play Award, the Dublin Theatre Festival Best New Play Award in 1994 for The Mai, a McCauley Fellowship, a Hennessy Award, the Susan Smyth Blackburn Prize, and an E.M. Forster prize from the American academy of Arts and Letters. She is a member of Aosdána and lives in Dublin.

Anthony Cronin is a poet, novelist, memoirest, biographer, and cultural critic. His many works include the novels The Life of Riley, and Identity Papers. His collections of poetry include Poems (1958), Collected Poems, 1950-73 (1973), New and Selected Poems (1982), The End of the Modern World (1989); Relationships (1992), and Minotaur (1999). His non-fiction includes Dead as Doornails (1976), Heritage Now (1982/1983), and Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist (1996). A play, The Shame of it, was produced in the Peacock Theatre in 1974. He has been associate editor of The Bell and Literary Editor of Time and Tide. In 1983 he received The Martin Toonder Award for his contribution to Irish Literature. He is a founding member of Aosdána, and lives in Dublin.

Roddy Doyle was born in Dublin and worked as a teacher before becoming a full-time writer in 1993. His novels are The Commitments (1987), The Snapper (1990), The Van (1991), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize; Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha (1993), which won the 1993 Booker prize; The Woman Who Walked into Doors (1996), A Star Called Henry (1999), and Oh, Play That Thing (2004). His drama includes War (1989) and Brownbread (1993), as well as The Family, written for television. He has written the scripts for films based on his novels, including The Commitments, The Snapper, and The Van. He lives in Dublin.

Anne Enright was born in Dublin and is a novelist and short-story writer. She has published a collection of stories, The Portable Virgin (1991) which won the Rooney Prize that year. Novels include The Wig My Father Wore (1995), which was shortlisted for the Irish Times/ Aer Lingus Irish Literature Prize; What Are You Like? (2000), which won the Royal Society of Authors Encore Prize; and The Pleasure of Eliza Lynch (2002). Her stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review and Granta. She was the inaugural winner of The Davy Byrne Award for her short story Honey. Her most recent work is a book of essays about motherhood, Making Babies (2004).

Hugo Hamilton was born in Dublin of Irish-German parentage. He has brought elements of his dual identity to his novels. Surrogate City (1990); The Last Shot (1991); and The Love Test (1995). His short stories were collected as Dublin Where the Palm Trees Grow (1996). His later novels are Headbanger (1996); and Sad Bastard (1998). He has also published a memoir of his Irish-German childhood, The Speckled People (2003). In 1992 he was awarded the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. He lives in Dublin and is a member of Aosdána.

Joseph O’Connor was born in Dublin. His first novel, Cowboys and Indians (1991) was shortlisted for the Whitbread Prize. This was followed by a volume of short stories, True Believers (1991) and four novels: Desperadoes (1993), The Salesman (1998), Inishowen (2000), and Star of the Sea (2002), which became an international bestseller and was published in 29 languages. It received the Prix Littéraire Zepter for European novel of the year, a Hennessy/Sunday Tribune Honorary Award, the Irish Post Award for Fiction, France’s Prix Millepages, Italy’s Premio Acerbi, A Nielsen-BookScan Golden Book Award, and an American Library Association Notable Book Award. His non-fiction includes Even the Olives are Bleeding: The Life and Times of Charles Donnelly (1993); The Secret World of the Irish Male (1994); The Irish Male at Home and Abroad (1996); and Sweet Liberty: Travels in Irish America (1996). He has written three stage plays: Red Roses and Petrol (1995); The Weeping of Angels (1997); and True Believers (2000). His screenplays include A Stone of the Heart; The Long Way Home; and Alisa. He has recently been awarded a Cullman Writing Fellowship at the New York Public Library.

Mary O’Malley was born in Connemara, Co. Galway and educated at University College Galway. She taught for eight years at the University of Lisbon before returning to Ireland in 1982. Her collections of poems are: A Consideration of Silk (1990), Where the Rocks Float (1993); The Knife in th

e Wave (1997), Asylum Road (2001), and The Boning Hall (2002). She received a Hennessy award in 1990. Her next collection is due from Carcanet in 2006. She is a member of Aosdána, and lives in Connemara.

Fintan O’Toole was born in Dublin. He has been a columnist with The Irish Times since 1988 and was drama critic of the Daily News in New York from 1997 until 2001. His books include The Politics of Magic: The Work and Times of Tom Murphy (1987); Ex-Isle of Erin (1997); A Traitor’s Kiss: The Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1998); Shakespeare is Hard But So Is Life (2002); After the Ball: Ireland After the Boom (2003); and White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America (2005).

Ann Saddlemyer is Professor Emeritus of the University of Toronto and former Master of Massey College, currently adjunct Professor at the University of Victoria. She has edited the letters and plays of J.M.Synge, the plays of Lady Gregory, and the letters of the Abbey Theatre directors. She is one of the general editors of the Cornell Yeats manuscript project, and is currently working on an edition of the correspondence between George Yeats and W.B. Yeats. Her most recent book is Becoming George: The Life of Mrs W. B. Yeats (2003) which was shortlisted for the James Tait Black award.

Colm Tóibín was born in Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford and is a novelist and journalist. His novels are The South (1990), The Heather Blazing (1992/1993), The Story of the Night (1997),The Blackwater Lightship (1999), for which he was shortlisted for The Booker Prize, 1999; and The Master (2004). His non-fiction includes Bad Blood (1994) and The Sign of the Cross – Travels in Catholic Europe (1994). He recently won the Los Angeles Times Novel of the Year for The Master, which was also shortlisted for the 2005 Booker Prize. He lives in Dublin and is a member of Aosdána.

Vincent Woods is a poet and playwright. He was born in Co. Leitrim and has lived in the United States, New Zealand and Australia. He worked as a journalist with RTE until 1989, when he began writing full-time. His radio play, The Leitrim Hotel, was a prize-winner in the P.J. O’Connor Awards for radio drama and his poetry collections include The Colour of Language. His plays include At the Black Pig’s Dyke (1992), John Hughdy and Tom John (1991), Song of the Yellow Bittern (1994), and A Cry from Heaven (2005). Among his adaptations and translations are Fontamara (1998) and Winter (2005). He has won the M.J. McManus Award for Poetry and is a member of Aosdána

Illustrations

Cover Watching the currach on its way to collect turf from a Galway Hooker.

From J.M. Synge, My Wallet of Photographs

Frontispiece J.M. Synge and Molly Allgood. Níl sí ag Eisteacht by Sean Keating PPRHA. Reproduced by kind permission of Sir and Lady A.J. O’Reilly. Copyright permission granted by the Keating Estate.

1 The Synge Family. (Seated, from left) Samuel, Mrs. Synge, John; ( standing) Annie later Mrs. Harry Stephens), Robert, Edward. From Edward Stephens, My Uncle John.

2 Druid Photo of Marie Mullan

3 Islanders on Inishere.

From J.M. Synge, My Wallet of Photographs.

4 Photo of J.M.Synge

5 Synge’s Paris: The playwright’s room in the Hotel Corneille, where he lived in 1896. Reproduced by permission of the Board of Trinity College, Dublin.

6 A Wicklow Tramp, possibly the old sailor described by Synge in his essay ‘The Vagrants of Wicklow’. From J.M.Synge, My Wallet of Photographs.

7 Riders to the Sea, 1906, with Maire O’Neill, Sara Allgood and Brigit O’Dempsey. Reproduced by permission of the Board of Trinity College, Dublin.

8 Synge with his mother, Rosie Calthrop (centre), and Annie Harmar, in the summer of 1900.

From Edward Stephens, My Uncle John.

9 ‘Selling on the Stones’, St. Patrick’s Street, before the market was closed by the Corporation in 1906. From J.M. Synge, My Wallet of Photographs.

10 Molly Allgood.

11 Druid Playboy Shot.

Illustration 1: The Synge Family. (Seated, from left) Samuel, Mrs. Synge, John; (standing) Annie (later Mrs. Harry Stephens), Robert, Edward. From Edward Stephens, My Uncle John.

1 New Ways To Kill Your Mother ~ Colm Tóibín

In 1980, having been evicted from a flat in Hatch Street in the centre of Dublin, I was offered temporary accommodation around the corner at Number Two Harcourt Terrace. The house, three storeys over basement, was empty, having recently been vacated by its elderly inhabitant. It was early April when I moved in and the cherry tree in the long back garden was in full blossom. Looking at it from the tall back windows of the house, or going down to sit in the garden under its shade, was a great pleasure. The thought might have occurred to me that whoever had just sold this house could be missing it now, but I don’t think I entertained the thought for very long.

The aura of the previous inhabitant of this house, in which I ended up living for almost eight years and where I wrote most of my first two books, appeared to me sharply only once. I was putting books in the old custom-made bookshelves in the house when I noticed a book hidden in a space at the end of a shelf where it could not be easily seen. It was a hardback, a first edition of Louis MacNeice’s ‘Springboard: Poems 1941-1944’. I realized that these shelves must have, until recently, been filled with such volumes, and that the woman who had left this house and had gone, I discovered, to a nursing home, must have witnessed a lifetime’s books being packed away, the books that she and her husband had collected and read and treasured. Books bought perhaps the week they came out. All lost to her now, including this one, which gave me a sense of her as nothing else did.

I asked about her. Her name was Lilo Stephens. She was the widow of Edward Stephens, the nephew of J.M. Synge. In 1971 she had arranged and introduced ‘My Wallet of Photographs’, by J.M. Synge. Edward Stephens, her husband, who died in 1955, was the son of Synge’s sister Annie. Born in 1888, when Synge was seventeen, he was aged twenty when his uncle died in 1909. Later, he became an important public servant and a distinguished lawyer. In 1921 he accompanied Michael Collins to London for the negotiations which led to the Treaty. He was subsequently secretary to the committee which drew up the Irish constitution and thereafter became assistant registrar to the Supreme Court, and finally registrar to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

In 1939 on the death of his uncle Edward Synge, who had not allowed scholars access to Synge’s private papers, Edward Stephens became custodian of all Synge’s manuscripts. He began working on a biography of his uncle, which would partly be a biography of his family. ‘I see J.M. and his work as belonging much more to the family environment,’ he wrote, ‘than to the environment of the theatre.’ He had been close to his uncle, having been brought up in the house next door to him and spent long summer holidays in his company, and been taught the Bible by Synge’s mother, as Synge had. But, in Synge’s lifetime, not one member of his family had seen any of his work for the theatre. At his uncle’s funeral, Edward Stephens would have had no reason to recognize any of the mourners who came from that side of his uncle’s life. For his family, Synge belonged fundamentally to them; he was, first and foremost, a native of the Synge family.

‘It was [Synge’s] ambition,’ he wrote,

to use the whole of his personal life in his dramatic work. He ultimately achieved this … by dramatizing himself, disguised as the central character or, in different capacities, as several of leading characters, in some story from country lore or heroic tradition. It is in this sense that his dramatic work was autobiographical and that the outwardly dull story of his life became transmuted into the gold of literature.

In his work, Edward Stephens ‘transcribed in full,’ according to Andrew Carpenter

many family papers dating back to the eighteenth century; he copied any letters, notes, reviews, articles, fragments of plays, or other documentary evidence connected, even remotely, with Synge. He also recounted, with a precision which is truly astonishing, the events of Synge’s life: the weather on particular days, the details of views Synge saw on his bicycle rides or walks and the history of the countryside through which he

passed, the backgrounds of every person Synge met during family holidays, the food eaten, the decoration of the houses in which Synge lived, the books he read, his daily habits, his conversations, his coughs and colds – and those of other members of the family.

By 1950, the typescript was in fourteen volumes, containing a quarter of a million words. On Stephens’s death in 1955, it had still not been edited for publication.

His widow, Lilo Stephens, inherited the problem of the Synge estate. Out of her husband’s work – ‘the hillside,’ as one reader put it, ‘from which must be quarried out the authoritative life of Synge’ – two books came. Lilo Stephens made her husband’s manuscript available to David Greene, who published his biography in 1959, naming Edward Stephens as co-author. Later, in 1973, Andrew Carpenter would thank her ‘for her patience, enthusiasm and hospitality’ when he edited her husband’s work to a book of just over two hundred pages, My Uncle John. In 1955, Lilo Stephens also had inherited Synge’s papers from her husband. They had been kept for years in Number Two Harcourt Terrace as her husband worked on them. In 1971, Ann Saddlemyer would thank Lilo Stephens for first suggesting the volume ‘Letters to Molly’ and providing ‘the bulk of the letters as well as much background material.’ Edward Stephens had purchased these letters from Molly Allgood so that they would be safe. Finally, Lilo Stephens ensured the safety of Synge’s entire archive by moving it from Harcourt Terrace to Trinity College where it rests.

The Magician

The Magician The Empty Family (v5)

The Empty Family (v5) New Ways to Kill Your Mother

New Ways to Kill Your Mother The Master

The Master The Heather Blazing

The Heather Blazing Brooklyn

Brooklyn The Blackwater Lightship

The Blackwater Lightship The South

The South Lady Gregory's Toothbrush

Lady Gregory's Toothbrush House of Names

House of Names Mothers and Sons

Mothers and Sons Synge

Synge The Modern Library

The Modern Library The Testament of Mary

The Testament of Mary Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know

Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know Nora Webster: A Novel

Nora Webster: A Novel